Visit to Virginia, Summer 2021

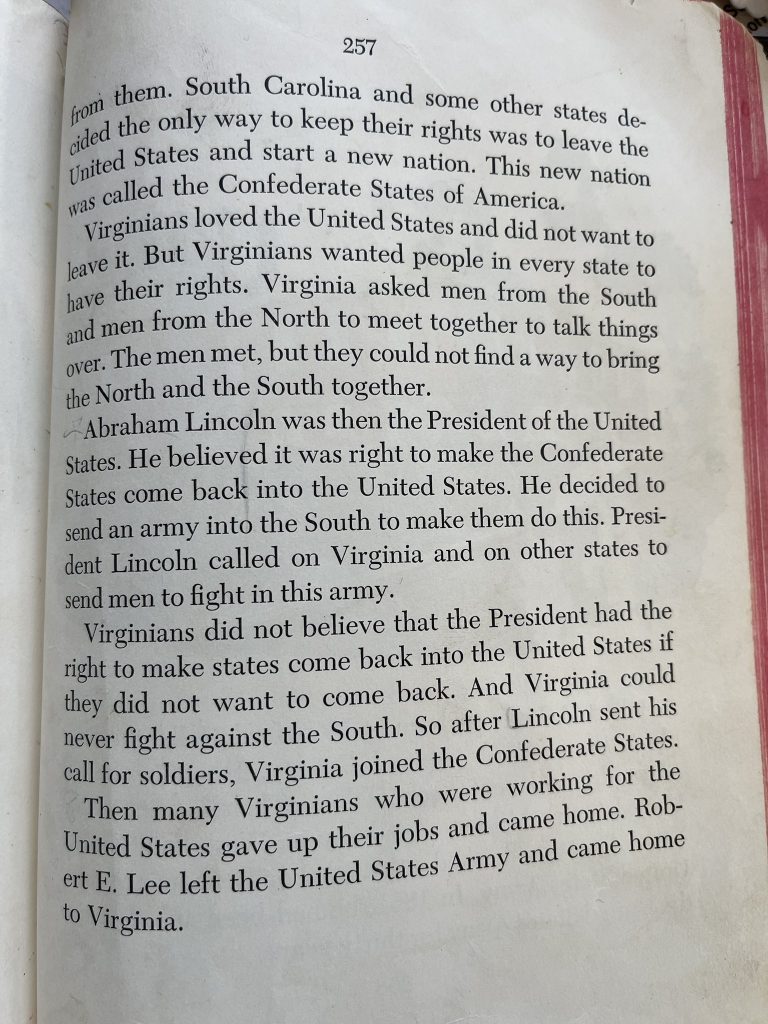

For a few years now, as the Black American experience has become more a part of the national consciousness, and mine, and as the debate over Civil War monuments have taken hold, I’ve been telling my friends in Philadelphia that I was taught in my Virginia elementary school that soldiers like Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson were heroes. They are dismayed at hearing that and I’m appalled that’s what I was taught.

Coincidentally, my fourth grade Virginia history book recently showed up on my Twitter feed. At first, I had the warm feelings I get when I run across a piece of culture from my childhood.

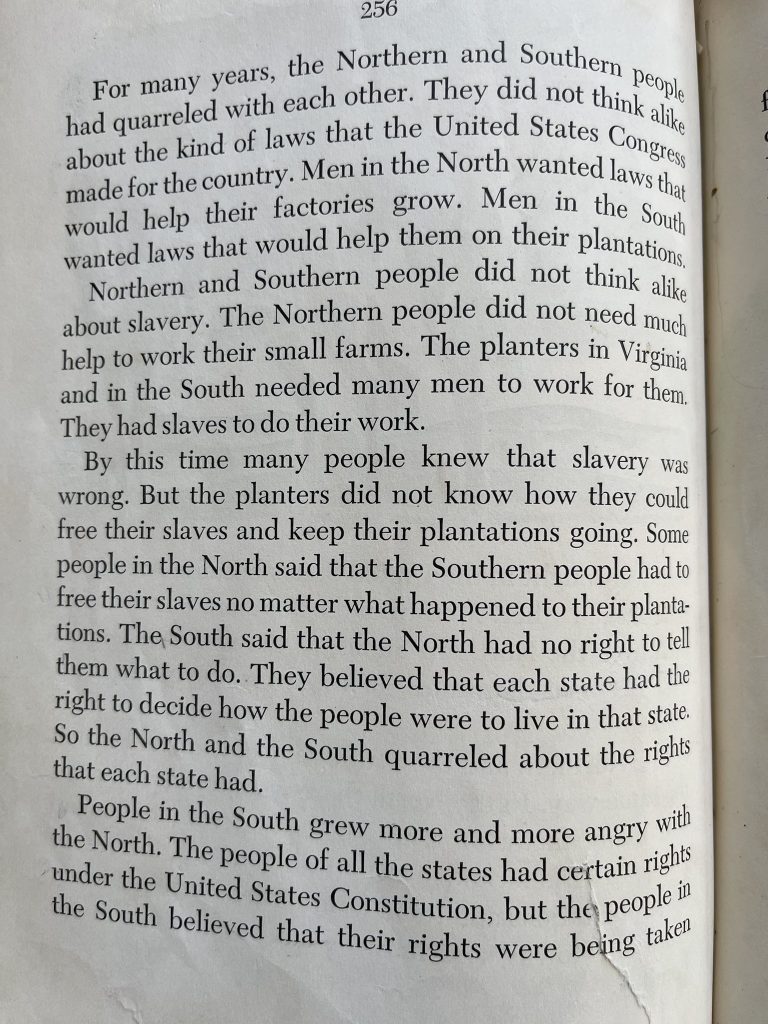

But as I dug deeper, and looked at the book through adult eyes, I was more than appalled. I’m not an American history scholar, but I know enough, and I know that the war was fought over slavery. This textbook makes the case that the Civil War was fought over states’ rights.

From the book: “The South said that the North had no right to tell them what to do. They believed that each state had the right to decide how the people were to live in that state.” Of course, “the people” in Virginia didn’t include Black people.

It gets worse and weird.

I found the book on Amazon and it is selling for a high of $1,601.10. The cheapest book is for sale at $399. Why? Who is buying it?

It being Amazon, there are reviews, but only a handful and generally from people like me who had the book in the fourth grade and shared a memory or two. And then there is “Busy Lady” who gave the book five stars and wrote, “I had this book as a fourth grade student. Later taught from this book as a 4th grade teacher. Good beginning history book. Written like a story.”

According to the Tweet, the book was published in 1956, so it’s understandable, not justifiable, but understandable, that it was still in use when I was in fourth grade in 1968.

I don’t know when the book was phased out (I hope it’s not being used. It can’t be. Right?), but we can guess that Busy Lady, who wrote the review in 2018, was teaching in the 1980s and perhaps in the 1990s, and possibly later. It certainly doesn’t speak well of the history teachers being hired in Virginia. Busy Lady taught bad history, still doesn’t recognize that, and there are, I fear, many more like her.

Thankfully, the Black community and allies have had enough of this whitewashing.

While I was visiting family in Richmond in July, we went to take a look at Monument Avenue, which used to be lined with statues representing members of the Confederate military: J. E. B. Stuart, Stonewall Jackson, Jefferson Davis and Matthew Fontaine Maury. All four were removed from their memorial pedestals amidst civil unrest following the May death of George Floyd and I say, “about time.”

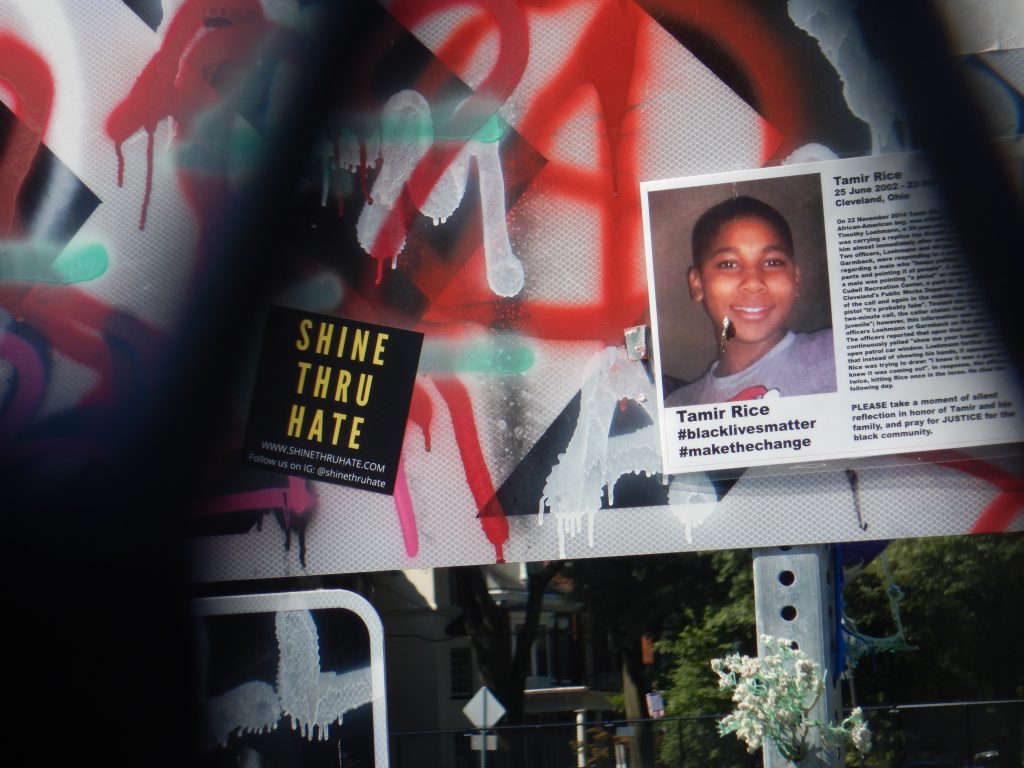

The monument to Robert E. Lee is still up. I was unexpectedly moved by a swirl of reflections seeing the statue in its graffiti-scarred condition along with the racial justice artwork that had been placed around it. I thought about the history I was taught, that these men should be venerated when they were traitors. I was saddened thinking about what the Black community of Richmond had to bear living among these monuments to men who supported slavery. And I was proud that activists whose anger had been pent up too long exclaimed, “enough,” and made it clear through words and deeds that it was time for those statues to be gone.

According to Wikipedia, “In the wake of protests, the graffiti-covered [Lee] monument increasingly became a venue to portray images of racial justice and empowerment: from ballerinas dancing at the base of the plinth to video projections of George Floyd, Malcolm X, Angela Davis (and others) onto the statue itself. In October 2020 the graffiti-covered monument was deemed among the most influential American protest artworks since World War II by the New York Times.”

Over time, the site became a site of community celebration and a place to gather, with people grilling while communing. There was a basketball hoop and a voter registration table. It felt great, knowing that something good came out of something bad.

Virginia Governor Ralph Northam has ordered the statue’s removal but it is being contested in court.

In general, I’m not in favor of destroying monuments. I think signs can be erected to contextualize them. Or monuments can be displayed in a museum where, again, the story of the history behind them can be told.

In this case, I would love for the statue to remain as is because of the story it tells as it stands. That is, the monument was erected to commemorate the Confederacy. Now, it signifies a time when right-minded people declared the statue inappropriate, to put it mildly, and most definitly not a reflection of what America can and should be. A place where all people are treated equally and racists are given no harbor.

But that’s not my decision to make. Whether it stays or goes, its presence, or lack thereof, will symbolize a new, and I hope, better era for America.

The trip wasn’t all about history. After leaving Richmond, I headed to my hometown, Virginia Beach, for some R&R. Every year when I visit, my brother Mark and I take a road trip and explore someplace. This year, we visited the towns and villages of Virginia’s Eastern Shore.

We didn’t order minnows with our lunch at this joint in Wachapreague.

First stop, Kiptopeke State Park, where we saw ghost ships. During the height of WWII, the U.S. Maritime Commission awarded Matthew H. McClosky, Jr., a Pennsylvania businessman, an initial $7 million contract for development, and later a $30 million contract for the construction of these ships. Before the war’s end, 24 would be built.

His company, McClosky & Company, opened up a shipyard in Tampa, Florida where the temperate climate was just right for building ships out of concrete. Wartime shortages of steel required the ships to be constructed using ferrocement, which used layers of wire and rebar mesh in the concrete for cohesion. This prevented cracks from forming and allowed for the ships to be built in record time.

The ships saw active service in the South Pacific; two participated in the allied invasion of Normandy. One ship served as a training ship on the West Coast; another collided with a concrete steamer and was laid up in Bermuda for repairs.

In 1949, nine of the ships were towed from berths in Norfolk and Texas and sunk to create the breakwater to protect the ferry dock at Kiptopeke.

This information about the ships and more can be found at Ghost Ships of the Eastern Shore.

We also visited the village of Saxis, which has a population of about 200 in the summer and 100 in the winter. It’s not the kind of place I’d like to live in but it sure was an attractive town.

In 1990, softshell crabs were the mainstay of the Saxis economy, with as many as 8,000 dozen a day (250,000 dozen a year) shipped fresh and frozen to such distant places as the West Coast and Japan.

In 2012, Hurricane Sandy swept away all but one crab house on the Creek Point, according to a brochure given out in a tiny little historic shop, which had been turned into a museum.

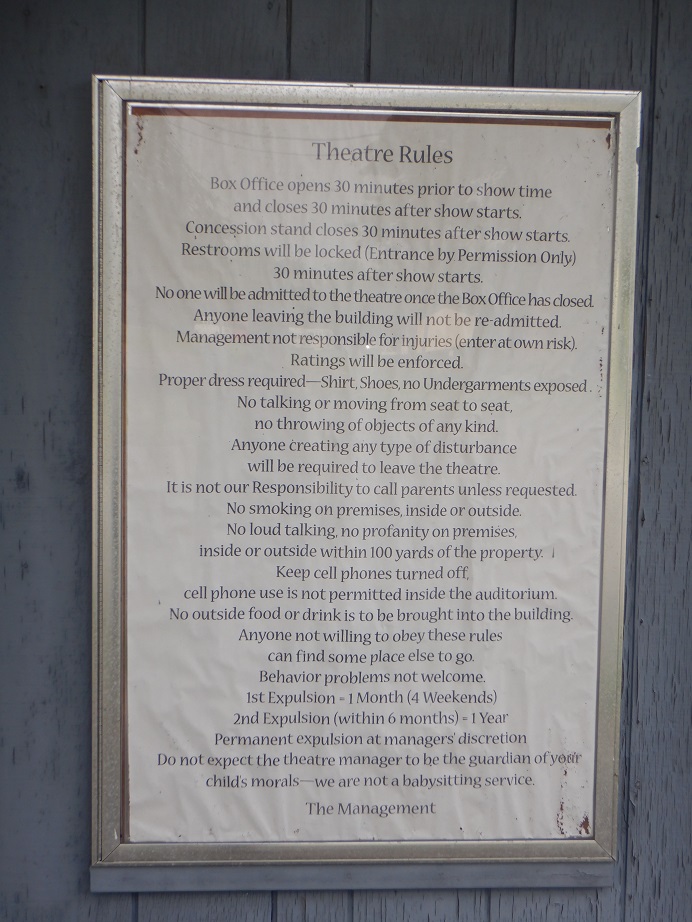

On some back road we stumbled upon this splendid dilapidated movie house. It was hard not to imagine this theater as a beauty in its heyday and the role it played in the community. In its ramshackle state it looks like it could have been shut down for 50 years, but it couldn’t have been closed that long. The sign out front, which is remarkably, somewhat intact, tells patrons to “Keep cell phones turned off.”

Movie-goers there seemed to have been a particularly rowdy bunch. Other rules and messages on the sign were: “Managers will not be responsible for injuries (Enter at your own risk)”; “No throwing of objects of any kind”; “No loud talking, no profanity on premises inside or outside within 100 yards of the property”; and “Do not expect the theatre manager to be the guardian of your child’s morals—we are not a babysitting service.”

My brother and I were content to wander wherever the road took us, but other than the ghost ships, there was only one other site I wanted to see, the grave of Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, who wrote “That’s All Right, Mama” “My Baby Left Me” and “So Glad You’re Mine,” which were all recorded by Elvis Presley and other musicians. Later in life he moved to the Eastern Shore where he died in 1974 in Nasawadox.

But the grave did not want to be found. Information about where he was buried was sketchy and sparse.

One internet site said Crudup was buried at Bethel Baptist Church in Franktown. We found the church, which was cool and historic in its own right. There were graves on the church’s grounds but not Crudup’s.

We pieced together some other clues from the internet but they led to nothing but dead ends. Stumped, we headed back to the church to figure out our next step.

In the church parking lot was a man in a pickup truck and so we asked him by chance if he knew where the grave was.

Not only was he a church trustee, his father was buried in the cemetery and he was going there to check out some recent landscaping done there. Serendipity and salvation!

Five minutes later we were at the cemetery.

Mission accomplished and that’s alright so we headed back to Virginia Beach.

-30-

Great read,thanks you!